- Home

- McKenzie, Duncan

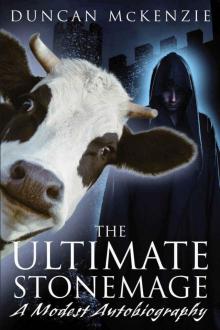

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography Page 3

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography Read online

Page 3

I instantly fell upon the deck of the ship, reduced to tears, and my weeping continued unabated until the town of Luthen was just a shimmering spot upon the horizon, and its song was nothing more than a faint pulse, growing and fading with the wind.

We sailed on at a gentle pace, for, having completed such a great and arduous labour, I wished to relax for a time and felt no need of haste. We meandered along the African coast, and I whiled away the hours delighting in the variety of exotic birds and animals I could see among the trees, and sometimes shooting them with my bow.

After five days of this pleasant life, we came upon a fishing boat, and I called out our greetings to them. The pilot answered in kind, then asked us where we were bound.

“Ubari.”

“Ah, it is but a few hours further. And whence do you sail?”

“Out of Luthen.”

“Could it be,” he asks, “that you are a builder from the east?”

“I am,” I told him.

“Then I advise you to steer clear of Ubari, for twenty fast warships lie in wait for you there, with orders to catch you and to hang you.”

This was scarcely to be believed! I asked the fellow: “By whom were these orders given?”

“By Gavor Hercules. It seems he is angered by certain singing towers.”

You may imagine my dismay at this news. I paid this fisherman twelve arrans to keep his silence, then we quickly turned north and west, at full sail, away from Ubari.

As we sailed, and my shock faded, I considered the unfolding of events, and soon the truth of the matter struck me with such clarity it could not be doubted. If you will consider the following scenario, I think you too will appreciate its validity.

It was early morning on the day of my departure from Luthen. Gavor Hercules was sleeping in his chamber, when a soft and lovely sound filled his ears. He rose, on those ancient, noble legs, and walked to his window. There before him he saw such visions of beauty as he, with his warlike disposition, had not the words to describe.

In the streets below, he saw the townspeople were assembling, clutching their hands in wonder at the shimmering array of lights which now bathed their once-drab town. Even as he watched, the townsfolk spontaneously started to sing the praises of their lord, and perhaps of myself for being the creator of these lovely buildings.

Gavor Hercules was overcome with childlike serenity, his old heart bursting with joy and love.

But his followers, murderers and pirates all, were horrified at this change in their master. They said, “The old man is so filled with love he will lose the will to fight, and we will lose the gold and booty we gain from our wicked acts.”

They secretly set out in their ships to take their revenge on me, claiming Gavor Hercules had sent them. And they attacked the towers with siege engines, and when these great weapons did nothing to harm the structures, they hired corrupt wizards to remove their mighty bonds. No sooner had one tower collapsed than the bindings between the towers, intended to strengthen them, caused the others to collapse, and this in turn destroyed the scores of surrounding buildings to which I had so carefully anchored the towers.

In the meantime, they murdered sweet Gavor Hercules as he slept, but told everyone he had died of old age.

I have since found numerous witnesses who have sworn to me the events which transpired in Luthen at that time were exactly as I have described, or, at the very least, they could not prove otherwise.

Gavor Hercules did die, and it was indeed claimed he had died of old age, even though he was obviously murdered. I have consulted seers and augurs, and they all confirmed my interpretation of events was the true one.

As I sat aboard my ship and realized the danger facing me, I knew it would be mortal folly to remain in the Mediterranean, for there were close to a hundred raiding ships in his force, all looking to take my life. I knew, too, I could not hope to round the west coast of the Spanish peninsula, for the sealord’s largest warships travel those routes in order to exact tribute from ocean traders, and I would surely be sunk long before I reached Ceol.

No, only one option remained: I must set sail to the continent of America, where I might take refuge for a time. So, westward I sailed, and by night my vessel slipped silently beneath the great Gibraltar Bridge which separates the sweet waters of the Mediterranean from the cruel Atlantic Ocean.

The Second Part

In Which I Tell Of My Visit To The Duck Islands And My Victories There

After some five days of westerly sailing, in good weather, we sighted land. I was concerned at this, for I knew it was at least six weeks’ voyage to the continent of America, and I feared we might have made some navigational error and turned once more to the Spanish coast. My slaves, however, assured me in the most earnest tones this was not so and said we were approaching the Duck Islands.

Few people have heard of these islands, and some people have expressed to me their disbelief the islands even exist, for they can be found on very few maps. I can understand such scepticism, for I had never heard of the islands before I encountered them. Nevertheless, I will tell you the Duck Islands most certainly do exist and lie some four days’ fast sail due west of Askar. If you read Nethercott’s account of her travels, you will find them mentioned peripherally on two occasions, and they are also listed in the Lotus Compendium, although I do not remember the precise citation. And if still you doubt, I can only advise you to hire a ship and follow my route, and you will certainly see them for yourself.

The slaves told me the Duck Islands would be an excellent place to pick up further supplies, for, as you will remember, my intended destination had been Ubari, which is but a few days’ sail from Luthen, yet I now faced a much longer route.

You may think me foolish for attempting the onerous voyage to America without first giving heed to the state of my supplies. Why, you may wonder, could I not have quickly put in at one of the small ports or islands along the coast of Africa? And in the normal way of things, this would indeed have been a wise strategy. However, during my ten months in Luthen, I had learned much about Gavor Hercules and his fierce captains. They were craftsmen of sea warfare, merciless and resolute in their pursuit of their enemies. My ship was fast, it is true, but his warships were still faster, and it would have been reckless of me to delay even a few more hours before making my escape to the west.

In the second place, I should point out my ship was well prepared for a long voyage: it had been designed as an ocean trader; the crew were familiar with the routes; and my larders were stocked with enough food for six months or more.

Now, I imagine, a second question will come to you. Why, you will ask, did this man Yreth take a six-month supply of food for a journey of just a few days?

I will explain. When I decided to leave Luthen for North Africa, I carefully considered the various conveniences and inconveniences my destination would afford. In most ways North Africa is a civilized land, but in its food customs it is little short of barbaric. Much of the local diet consists of roots, or leaves, or seeds, with precious little meat. And on those rare occasions when meat is served, it is usually such a base kind as mutton or goat, and is flavoured with herbs of the most disagreeable nature, which hide the poor quality of the meat and impart to it a fiery and mouth-numbing taste. By contrast, the meals I received in Luthen (and elsewhere in Spain) were usually of the highest quality—tender, bloodied meat, with rich, thick sauces—and certainly as good as anything you will partake of in the feasting halls of Cyprus.

So, before my departure from Luthen, I purchased large quantities of various salted meats, dried fruits, and some of my favourite preserves. I took enough for my intended stay in Ubari—in all, about six months’ supply. I had also purchased six vats of wine, five vats of strong Spanish ale, and one vat of wince, a delicious fermented drink made from onions. I had intended these for trading, as I am not given to take large amounts of str

ong drink, but now they were assigned to the provisions for my voyage.

So, in most respects my ship was well fitted for an ocean journey. In most respects, save this one: I had only a few days’ supply of fresh water. We had left Luthen with but a single barrel, and, since I place a high value on cleanliness, I had already used most of this in the natural course of my washing regimen.

However, there are many in Luthen who drink nothing but ale, and I believed I could subsist in the same manner during the weeks ahead, provided I drank only moderately and was willing to endure a week or so of light-headedness (for after that long, I am told, the constitution adapts naturally to drunkenness, and the ill effects are no longer felt).

The slaves also required small quantities of water. In their case, however, they could happily survive on sea water for a month or two. As for food, they needed only small quantities of the acorn paste which is favoured by their species, and I had plenty aboard.

Therefore, my first instinct was to turn away from the Duck Islands and continue west, for it was possible enemy ships might be waiting for me there, as they had been at Ubari. But the head slave said that, for an ocean voyage at this time of the year (it was then late in the autumn), the ship’s chank hull should be treated with willow wax. This wax could be bought on the Duck Islands, and at a good price too. It comes not from the willow tree as you might suppose, but from a species of fast-growing fern, and protects the chank from blistering in the cold water.

“Could such blistering cause this ship to sink?” I asked.

“Indeed no, sire,” he replied, “but the damage is unsightly, impossible to repair, and will certainly reduce the value of the vessel.”

“The ship will have little enough value to me if I am caught and hanged,” I replied. “No, let us continue west.”

“I am yours to command, sire,” he said. “Finally, I have recently been examining the dispositions of the clouds and seabirds, and these portend a great tempest, of the most powerful and destructive nature, within the next two days.”

It is very typical of slaves to leave the most for the last. Since I had no wish to venture on in a storm if this could be avoided, I yielded and ordered the slaves to steer towards the Duck Islands. It was well I made the choice, for the storm struck just a few hours after our landing, and it was one of the most furious I have ever witnessed. It tore the roofs from houses and wrenched large trees from the ground, roots and all. Even sheltered down in the harbour, my ship suffered a broken mast, and I am quite certain that, had I not decided to seek shelter, we would have been destroyed at sea.

As to the place itself, there is little enough to tell. The islands are small and rocky, with just a few hundred inhabitants apiece. From my conversations with the local folk, I learned that most were fishermen and fisherwomen, and the fish they caught were sold for a high price to those who lived in the lands to the east. However, since the trading ships from those lands arrived at the Duck Islands at the rate of perhaps one ocean trader every two or three months, and since the inhabitants of those islands never ventured more than a few hours’ sail from their own shores, I am at a complete loss to explain how this trade in fish took place.

The chief citizen of these islands was an astronomer by the name of Yorke who had come there from the Ten Mountains. Upon my arrival, he invited me to his mansion, and from there we watched the furious storm unleash itself. The next day, he set himself completely at my service, ordering for me a suitable quantity of willow wax, making me a gift of a great-sail, sending to my ship ten barrels of fresh water, and also sending helpers to inspect the broken mast on my ship. I, in my turn, made certain structural improvements to his mansion, and also gave to him my vat of wince. It was a gift he received with much joy—as well he might, for the onion vineyards of Luthen are among the finest anywhere.

The head slave told me the damaged mast could not be repaired in this port, and Yorke’s helpers confirmed it. They advised me to sail a few miles to the north, to the town of Leaf-of-Mint on the island of Tip. (Tip, of course, is one of the Duck Islands. The others are Tenatee, Rass Sholloy, and Trubear. We had put in at the last of these, at its only town, which bore the amusing name of Lyce.)

You may guess I was very reluctant to further delay my escape to the west by taking another side-trip; however, Yorke told me it would be at least another day, and perhaps two, until the large quantity of willow wax which my ship required was ready. Further, the head slave told me, if we were to sail with the broken mast, our voyage would take twice, or perhaps even three times as long. Naturally I was not anxious to sail west in a crippled ship, especially with fast warships in pursuit, so, once again, I capitulated, and we sailed the short distance to Leaf-of-Mint.

Tip is the largest of the Duck Islands and heavily wooded. After docking at Leaf-of-Mint, we found a community of carpenters, who agreed to carry out the necessary repairs in exchange for ale. Of course, I stipulated the ale should be delivered only after the mast was crafted and installed, since I did not want drunken carpenters shaping my new mast. After initial resistance, they finally acceded to my terms, and a tall pine tree was selected and cut down for the mast.

I will not describe more of the island of Tip, nor of the town of Leaf-of-Mint, since these places do not rate an important place in my tale, save only for the fact that, while I was there, I was removed from the dramatic unfolding of events back at the town of Lyce.

Suffice it to say I remained in Leaf-of-Mint only long enough for the repairs to be negotiated and completed. This came to three days. I mostly remained aboard my ship in my cabin, since no suitable accommodation was available in the town. The buildings were chiefly huts, made of logs or stones, and there were few features of note, save for a long wooden pier, to which my ship was moored. There was also an old white church in the centre of the town. The town itself is built in a natural inlet, and is surrounded by cliffs on three sides. Steep roads are cut into these cliffs to allow the transportation of lumber from the forests above. You may be sure watching this lumber being moved is the only entertainment you will find in this desolate town, unless you enjoy standing on the rocky beach and throwing pebbles out to the sea.

But there, I have said more than enough about Leaf-of-Mint and we will now leave the subject behind.

After three days, then, at Leaf-of-Mint, the mast was completed and installed. For this task, the local people assembled large cranes, made from pulleys and long beams, and the mast was hoisted from the cliffs, over the town in stages, to my ship. During this process, the beams supporting the mast were variously swung forward, or tilted forward through the use of ropes. By this method, and by alternating which pairs of beams held the weight of the burden, the mast was carried to the ship as if on giant legs.

During the first stage of the conveyance, the mast was “walked” over the graveyard near to the church. From there, it was taken over several houses, and, at one point, when the workers on the ropes decided to rest, they gently lowered the mast so it lay on the roofs of two huts. I should rather say, on the remains of the roofs of two huts, for the town had suffered damage during the recent storm. Then, after the workers had rested for a time, the great mast was raised once more, and continued its walk towards my ship.

On reaching the pier, the “legs” were brought very closely together, and, swaying precipitously, the mast was walked down the pier and alongside my ship. Next, the two forward legs, which had been notched at their base, were fitted over the edge of the pier, and lowered towards the ship, while the rear legs were swung around at ninety degrees, then pulled in the direction of my ship. This action had the effect of tilting the mast.

Little by little, the mast was moved towards the hole which the damaged mast had occupied. Try as they might, however, the labourers were unable to fit the mast into the hole at an angle steep enough to allow the mast to slip in. This was because the mast was very much taller than the legs which suppor

ted it. Finally, the workers took the mast away again, using the same wooden legs, and proceeded slowly back across the town. When they reached the cliffs once more, they stopped to reassess the situation.

The enthusiasm and vigour of these people was certainly noteworthy; however, I was pressed for time, so at this point I sent out my slaves, telling them to remove the mast from the complex assembly of beams and ropes, and to transport it back by carrying it in the normal way. This they did, carrying it through the town with the greatest of ease. We quickly installed the mast into the deck of the ship, then set sail back to the town of Lyce, our efficiency bringing astonishment and perplexity to the people of Leaf-of-Mint.

As I write this now, it occurs to me I did not remember to give the townspeople the ale I had promised them in payment for the mast. The oversight, however, was an honest one.

When we arrived back in Lyce, we found our tubs of willow wax waiting for us. My crew instantly set about smearing the substance on the ship’s white hull. Since I found the smell of the fresh wax disagreeable, I used the time to pay a farewell visit to the astronomer Yorke.

On entering his mansion, however, I was met with the most mortifying sight. Sitting with Yorke, apparently as guests, were a number of seafarers wearing the colours of Gavor Hercules. The leader of these I knew well, for he was the nephew to the lord, as well as being his lieutenant-in-chief. His name was Panka, but he was known to all as The Spear, and he had been a regular guest at the lord’s dinners. Of course, he recognized me immediately, and cried out to his men to seize me, which they promptly did.

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography