- Home

- McKenzie, Duncan

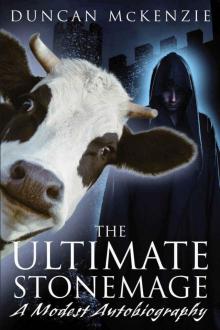

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography Page 2

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography Read online

Page 2

As I walked about my ship, I was filled with joy at the magnificent gifts I had received. I saw I had been wrong to fear and despise Gavor Hercules. I knew now that, despite his fearsome reputation, he was a man of wisdom. He had made a generous payment to me, and I vowed to give my new patron the full value of his coin.

That evening, as he had promised, Gavor Hercules invited me to his dining room. At least twenty people sat at the table. At the head, of course, was Gavor Hercules himself. At the other end was his consort, Chryse, and between them the guests were arranged in the usual way, which is to say, according to the degree of their favour with the lord. Those most highly regarded were seated closest to him; those least regarded were furthest away, although, of course, their presence at the table at all was nonetheless a great honour.

As I entered, I made to take a seat at the most distant chairs, but the lord called out to me and said: “None of your modesty, Yreth! You must sit on the chair closest to me, on my right side.”

The dinner itself was delicious, and the foods seemed all the more succulent to me when Gavor Hercules told his other guests about the strange negotiation he and I had undertaken, and how deeply he was impressed by my character. As I heard his appreciative words, I could only nod and weep with joy.

The next day, I went to the tallest of the towers and examined the binding wefts of this ugly structure. As I expected, it was held together by a few cross-bindings. (If you do not know, these are invisible gossamers of force which function like a sturdy beam between two walls or like a pillar between floor and ceiling.) The cross-bindings had been badly placed when first created, and had also become bent and decayed with age.

Yet as I examined the enchantments more closely, my scorn changed to puzzlement for the composition of these spells was unfamiliar, and I could not identify their type. They were clearly very ancient, and I wondered if this was some powerful enchantment whose secrets were lost in antiquity.

At this point, an impatient stonemage would have laid down new bindings, to reinforce the ones that were failing. Indeed, I had several times raised my arm to cast new spells, but each time I did so an inner voice spoke to me, saying, “Yreth—stay your hand! Solve the mystery before you! Understanding must precede action!”

Suddenly, in a flash of inspiration, I realized the bindings before me were that contemptible type known as the Struts of Atlas, but so badly distorted their form was barely recognizable.

From the grand name, you would think Strut of Atlas a strong enchantment, but it would be better named the Bane of Atlas, for instead of holding your world aloft, it is more likely to bring it tumbling to the ground! It is a crude, treacherous and unstable spell, given to collapsing in a violent manner, and its use is the sure mark of the untrained builder.

But woe to the stonemage who thoughtlessly tries to replace or remove the Strut of Atlas!

I knew one boastful fellow back in Cyprus who had learned a spell or two and fancied he could amaze the world with his powers. He had little training in the arts of the stonemage, but he set about repairing a certain feast hall—against my advice. He detected the presence of a distorted Strut of Atlas. The strut supported a ceiling, and he decided to shore it up with a second beam of greater strength. But he had no sooner placed the preliminary runes than the Strut of Atlas collapsed, its ends snapping powerfully together. Instantly, the ceiling above him was pulled down with great force, and he was crushed and killed by the huge stones. As they say, live a fool’s life and you will die a fool’s death.

No, be counselled by me, replacing the Strut of Atlas requires the utmost care and caution, and it is often better to leave the wretched enchantment in place and do what you can to repair it than to try replacing it.

I am sure if I had tried to cast new cross-bindings in that tower in Luthen, the precarious struts would have collapsed, destroying the tower and killing me. But my wisdom, insight and restraint saved me then, as they have often done since.

I set to work repairing the vile Struts of Atlas. With great care, I used an ivory turning wheel (together with the resonating whistle) to twist the coils, bringing the strut’s central wefts back into alignment. A little dab of acorn oil upon the base rune ensured the roots of the treacherous spell would stay firmly within the stones for the present.

The tallest tower contained fifty-one Struts of Atlas. I tightened them one by one. In just a few hours, I was able to reverse the warping effects of centuries.

As I worked to make these adjustments, the stones of the old tower rumbled and scraped, the walls twisted, and pieces of dust and grit showered down from the exterior walls onto the streets below. Of course, these are the usual signs of a stonemage at his craft, but the townspeople of Luthen were not used to such work, and the transformations caused them the greatest alarm and wonder. When I emerged from the structure, I found a crowd of several hundred waiting outside, gazing in slack-jawed astonishment at the tower and its newly straightened walls.

As I walked down the steps, the people moved aside to make a path for me, and from their faces you would think I had changed their tower into an onion or caused a rain of dragons or some other such miracle, rather than adjusting a few invisible struts inside an old stone ruin.

I proceeded to the next tower—the short tower in the wall. The crowd followed me inside the building, lining the spiral staircases and watching my every movement as I carried out similar repairs to those I have already described for the tallest tower.

I had originally estimated the repairs would take four days or so, but it soon became clear to me the job was simpler than I had first supposed. The small wall tower, for instance, contained just ten cross-bindings, and no other bindings of any kind. Can you imagine a great structure here in the east being held together by just ten bindings? I have seen children’s play huts with more sophisticated work! In any event, it took me just half an hour to finish work on this tower—and this despite the presence of all those jostling bystanders on the spiral stairs. By the end of the day, I had repaired all five towers.

That evening, I dined once more with Gavor Hercules. By then, news of my work was all over town, and, as you can imagine, it was the only topic discussed over dinner. Gavor Hercules and his guests repeatedly asked me to explain the procedures I had used to carry out the work. Their interest pleased me—although they seemed to understand few of my answers, and I soon grew fatigued by their slow-witted questions.

Hercules congratulated me on the speed with which I had completed my work. I quickly explained my work had hardly begun, and there were numerous and complex structural modifications which must be made to the towers.

He told me then about the very ancient history of the building, and of their superb, solid construction. You can imagine well enough what I thought of his opinions, and the age of the towers was no excuse for their extreme ugliness. Still, I said nothing, but merely listened politely as his lordship, and then his various fierce captains and warriors spouted their tiresome theories about “good, solid stone.”

I politely gave them half an ear, but in my mind I was considering another matter. For I was determined to carry out a far greater transformation than merely straightening the towers. I wished to turn them into objects of true beauty. My problem was that Gavor Hercules did not want extensive changes, because such warlike men have no architectural vision and cannot imagine how a finished structure will look. The moment I started demolishing the stones of his towers, he was certain to object and stop my work. But I knew he would be delighted once he had seen the completed towers. So how to proceed?

As I sat at dinner, deep in thought, a unique solution occurred to me, in the form of three omens.

First, my eyes fell on a design in a silver goblet in front of me. The pattern was of a butterfly. Then, a few minutes later, I noticed Gavor Hercules’s consort, Chryse, looking in my direction, and as I thought of her name, I was reminded of the word

“chrysalis.”

There was a third omen, too, but I forget now what it was. Something or other to do with metamorphosis or butterflies I think.

In any case, the image came into my head of a butterfly emerging from a chrysalis, and this was my inspiration! The towers would undergo a secret change, one which would remain invisible to all until the work was complete. I know this sounds impossible, but an ingenious method had occurred to me. The thought of it excited me so much it quite spoiled the rest of the meal. I yearned for the fine feast to be over, and for the night to pass, so I could return to my work in the morning.

The first thing, of course, was to remove those terrible Struts of Atlas, for I did not want them contaminating my work. It took me weeks of delicate labour to disassemble them safely, and in their place I cast Quater’s Firm-Beam, which a fine spell, very stable and durable.

On each of the towers I placed a temporary facade—a thin layer created using the spell Spicesheet. It creates a white shell upon a surface, as thin as eggshell, but very strong.

As I completed each area of gleaming Spicesheet, I placed a second enchantment upon it—the Persistent Mural, a well known illusion spell. The Spicesheet had the precise shape and texture of the granite stones underneath, and was hard and cold to the touch, while the Persistent Mural gave the exact appearance of the stone.

I placed similar facades along the inside walls of each tower, and connected the outer and inner facades with cross-bindings.

If can picture it then, the thick walls of each tower were now sandwiched between an outer and inner facade which closely resembled the appearance of the original tower. Within this facade—this “chrysalis”—I could make sweeping improvements to the towers without being detected.

If you wish to know how perfect these facades were, mark this: on the second or third week of my work, I was standing on a low scaffold, rubbing powdered cloves into the stones to create an area of Spicesheet, when Gavor Hercules passed by.

He said: “Have you altered this stone somehow?”

I replied in the only way my integrity would allow: “Yes, sire, I have.”

He said: “It seems to me it is slightly cleaner. And it has a lustre and a depth which before now it had lacked.”

I said this was certainly the case.

Then he placed his hand against part of the facade and smoothed it, saying: “How I love these old stones. Since boyhood I have known them, and in all my voyages I longed to return to them. I am well pleased with your work upon them now.”

You may be sure I was encouraged! If Gavor Hercules could take pleasure in what he thought was a slight “cleaning” of the old stones, his pleasure would be increased a hundredfold when he beheld the magnificent spectacle which I was working underneath.

Let me now reveal to you the nature of my work.

In the first place, I had applied many fire spells, heating the walls of the towers until rock melted and fused, turning ugly and irregular bricks into a smooth sheet of a glasslike material. I then placed hundreds of powerful spells through the walls of each tower—cross-bindings, Sheet Walls, Peregrine Clasps, and Lasser Spheres in abundance—creating a surface as strong as the finest armour.

For further strength, I bound the towers each to the other with Firm-Beams, so even if one were subjected to so much force it might fall, it would be solidly supported by the other four towers. Finally, I placed invisible Seizure Lines radiating out from the towers and attached to other buildings all over the town. Through these spells, my mighty towers would bestow some of their strength on the surrounding structures.

Having thus established the strength of my towers, I set about industriously fashioning their beauty. But in this, take note, I did not merely impose my own taste. It is important, when doing such work, to bear in mind the tastes and inclinations of the patron. In this case, Gavor Hercules was clearly a man of conservative taste, and the colours placed upon the materials of the towers had to be similarly conservative. With five towers, the choice was obvious: the five primary colours. Simple, elegant. One colour for each tower. So, the square tower in the castle I made a gentle green. The two round towers on the east corners of the castle I made yellow and peach. The small tower in the town wall I made beige. And the great tower in the centre of the town was a soft shade of purple.

I had decorated the interior of the towers, floors, walls, and ceilings with a deep red fur, spun, if you can credit it, from the rock itself. The making of this fur, which is called mashena, is not really a stonemage’s skill, but is a little trick I learned from an old instructor at Eopan. Unfortunately, it has become something of a lost art. Correctly spun, the fur is not only far softer than any animal fur, it is infinitely more durable, and also completely fireproof.

Even with no further changes, these towers would have been a worthy addition to any city in Cyprus, and certainly the wonder of the west. But I desired more than this: I intended to make these towers the wonder of the whole world.

To the outer wall of each building, then, I applied a range of transmutations, adding tubes and filaments of gold in a weblike pattern. Within the areas enclosed by this web, I created large glass jewels of all colours, so curved as to catch the rays of the sun and reflect them about the town, and so placed that, at any given time of the day, every area of the town would be bathed in beautiful colours. So you see, these towers would share not only their strength with the dull stone buildings of the town, but also their beauty.

Finally, and most wonderful of all, I had fashioned the walls of the towers so they were narrower in some places than others, in much the same way the sounding board of a well made violin is carved thinner in some parts than others. The slightest vibration on any of the buildings (caused, for example, by a light breeze, or the natural hubbub of the town) would set all these towers into a rapid vibration, producing a pure musical tone from each tower, and a lovely five-note chord from them all. Never, to my knowledge, had so delicate a construction been attempted.

As you may guess, this work, so simple in theory, was mind-taxing in its complexity. For the jewelled reflectors, I was obliged to make careful observations of the sun’s movements, ensuring my adjustments left no part of the town unlit. And the tones of the towers were so exquisitely interconnected that every slight tuning of one would send the others into a state of discord. And all this, working by touch beneath the stone facade I had laid. It was many months before these two jobs were completed.

In the meantime, I dined nightly with Gavor Hercules and quickly became a favourite within his circle for my tales of life in Cyprus. Frequently he would ask me about the wars being fought there at that time, or ask me if I knew of certain Cypriot sea captains. A strange aspect of this, which I have since observed in other warriors, is that Gavor might ask a question like, “Tell me, do you know of a fine commander by the name of Illian,” and from the tone of his voice I took this man to be some old comrade of his, and I would tell him what I knew of the warrior in question, and he would nod and laugh and make some remark such as “That rascal killed my son, you know,” or “Ah yes, he is a worthy enemy indeed.” On one occasion during my stay, one of these enemies actually came to visit Hercules, and I saw him treated with all the civility and generosity the lord extended to any of his merchant friends.

I could expound at great length upon various aspects of Gavor Hercules’s court, and upon the town of Luthen. I witnessed a thousand marvels and curiosities during my stay. However, I fear this would take me from the proper drift of my historical account, and these fascinating tales must be saved for some other time.

Finally, the jewels in the towers were perfectly placed, and the music of the towers was exactly tuned. The work had taken me, from start to finish, just over ten months, and was by far the longest commission I had yet completed. I was more than pleased with the detail of the work, but I found myself now facing a new problem. My work, you see, sat

isfactorily paid off my gift-debt to Gavor Hercules; however, if I were present when the true beauty of these buildings was revealed, it was likely he would bestow some further gift upon me. After all, this lord had paid me well over one thousand arrans for a simple repair task. How much more would he reward such elegant and scrupulous work as this? And if he gave me further payment, I would once again be indebted to him.

I resolved upon an ingenious solution. First, I placed Wefts of Sympathy on the facades of all the towers. Then I placed a matching weft on a brick to which I had also added a Spicesheet facade. I took this brick onto the ship which Gavor Hercules had given me as a gift and left it there.

Over the next few days, I made my farewells to all, explaining my work was now finished and I would be leaving shortly. Gavor Hercules implored me to stay, but I explained I had urgent business to attend to further south. He thanked me graciously for my hard work on the towers and made me a final gift of a fur cap and cloak. This, of course, was a token gesture only. The lord had seen no further improvement in his towers in nine months and naturally assumed the remainder of my work had been minor details. My debt was paid, then, and I was free to leave in good conscience.

Very early the following morning, I went to my ship and departed Luthen, bound for the city of Ubari in the kingdom of North Africa. When we were a mile or so from shore, I dissolved the magical facade on the brick I had taken with me. At once, the Wefts of Sympathy on the towers caused their facades to vanish, and at last those structures on which I had laboured so long were revealed.

The experience of seeing those dull chrysalises fall away to reveal the beautiful butterflies beneath is impossible to describe. The towers were ten—no, one hundred times more lovely than I had anticipated. Even the early rays of the sun were enough to catch the jewels of the towers, flooding the town in a brilliant pool of ever-changing hues. And the sound of their music was like angels singing from heaven—a perfect, unwavering chord. Though we were a mile from shore, I could feel the vibration of that divine chorus upon my chest.

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography