- Home

- McKenzie, Duncan

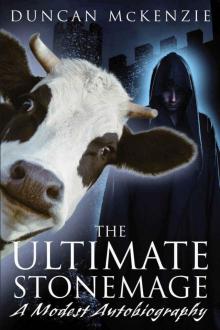

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography Page 6

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography Read online

Page 6

“The judges are the members of the town’s council,” he replied. “None are stonemages, but I have shown sketches of your proposal to them all, and they were unanimous in declaring the Grief a work without equal in this land.”

“Well, then, there is nothing to be feared by this course of action,” I said. “I am confident no stonemage might create so lovely a structure as my own. And if, by some miracle, one should create a work still more marvellous, why then, let that person take the commission, for he or she will certainly have earned it.”

“I see you are a man of the most perfect integrity,” he said. “And perfect judgement too! Very well, then—we shall have the competition as you suggest. And I shall sleep soundly in the secure knowledge your mighty Grief will win the contest and be built.” And at this we both raised our glasses and drank a toast to my Grief.

So the competition was announced, and several score stonemages of East America were summoned to Ramport for the purpose. On the assigned day, which was eight weeks after the conversation I have just recounted, exact models of the various designs, cast in plaster or lead, were placed in the Great Hall of the Round Fortress, which houses the administrative chambers of Ramport. Each model was placed upon a separate table, and the stonemage responsible for the design remained in front of its table in order to answer questions from the many people who had come to view the proposals.

Truly there were some attractive designs—although it is one thing to create a pretty model, and quite another to execute the plan on a grand scale—and I watched carefully as the townspeople wandered past the tables, nodding or smiling at the miniatures, for they were pleased by them. But as they reached the Grief, which I had sculpted in platinum and gold and then painted in lifelike flesh tones, and which stood more than twelve feet high, all were astounded and impressed beyond measure.

There were many high officials of the region present, and I spoke to some of them. A powerful merchant by the name of Ildreth told me he thought the design remarkable. The governor of North Pocern was there, and he nodded at me in such a way as to convey, without any possibility of doubt, that he thought my Grief to be one of the new wonders of the world. Also, I spoke with the Bishopa of Quebec, who had toured the hall with an entourage of several bishops and some thirty huge myrmidons. We talked very pleasantly, and she expressed her admiration for my daring model, saying that, in her opinion, it was certainly the finest design in the room, and she added that, if I ever sought work, I might presume upon her patronage.

Some hours later, before a large assembly, the winner of the competition was announced by the magistrate-in-chief. You will be astonished to hear that the council had selected not my design, but the design of a local architect. The work was a gaudy pastiche of the Far Western school, incorporating a fat central thimble-hall, surrounded by numerous nested towers, and various small houses, shops, and inns. As the magistrate read the decision, one could sense a great tension in the room, for it was clear to all present that a heinous injustice had been committed.

As you may imagine, I was outraged and insulted, and a mighty wave of fury rolled over me, for I knew who was behind this villainy—not only because of the warning in my vision, but also because Eon Vulpine was the only member of the council not present when the decision was announced, and this, I knew, was because his shame would not allow him to face the one he had wronged so grievously.

Therefore, I took my throwing-razor, which I carry always in my boot, and I placed it in my sleeve, then I quickly made my way to Eon Vulpine’s chambers, determined that, if his explanation of matters did not suit me, I should certainly take his life.

There I found him pacing back and forth in a state—so it seemed—of the utmost agitation. “Alas,” he said, as I entered the room, “what a disaster has befallen the town! To think we should have lost such a beautiful work.”

Now, this confused me and blunted my anger slightly, so I put aside my idea of killing him. Oh, what a cunning creature he was, for in speaking my own thoughts to me, as though he believed them himself, he made it seem as if my interests and his were one and the same.

I then asked him to explain why the competition had been won by a work which was so clearly inferior to my own. Could it be, I asked, the other officials had not in fact been as enthusiastically disposed towards my design as they had first pretended.

“Indeed, no,” he said. “The magistrate-in-chief, the purse warden, and the bishop all felt your design to be by far the finest. And as to my own feelings, you know them well.”

Here he broke into a powerful fit of weeping, so I was actually moved by sympathy for him, fool that I was, and I said: “This is a disaster for all. And yet, how do you explain this final verdict?”

“Our decision was overruled by a higher official,” he said. “The sentiment was expressed that it would be unwise to give so handsome a commission to a foreigner, particularly when many of our own stonemages, who have served us well, might relish the task.

“However,” he went on, “I was able to persuade the council to give you a commission of your own, a smaller version of the same magnificent design. It could be erected upon Paddle Island, which is the little island you see in the centre of the river. There it will serve admirably as a lighthouse, warning ships during foggy weather.”

A lighthouse! As I think back on the suggestion now, my anger rises, for I see Eon Vulpine was mocking me, extending the indignity of my defeat. Would that I had strangled him then and there with my bare hands, for his blood was not worthy to be spilled by my throwing-razor. Yet at the time, my own anger and disappointment were tempered by compassion for this treacherous, miserable creature.

“This is very much less than I had hoped for, and indeed, than I had been promised,” said I. “For you told me the competition would not take into account the nationality of its participants.”

“I share your disappointment,” he said, and he was all sympathy and comforting arms. “And yet, consider this: once people see the beauty of the lighthouse, they will clamour to have greater structures built by your hand—and with such popular support, it will be impossible for any higher official to oppose the construction. Further, I shall personally see to it that you are paid handsomely for the work—let us say, one thousand arrans.”

Now, in my state at the time, this seemed a generous price, for I knew a small lighthouse would be very much simpler to build than the great statue-tower I had planned. I accepted on the spot, requesting the funds be paid to me in advance, as a token of goodwill.

“Alas! With the limited power I possess, it is quite impossible for me to pay you this sum from the town’s treasury without further delays,” he said. “Therefore, I shall pay you this sum immediately, and from my own purse, for such is my great trust in your genius and your talent.” And with that he opened a trunk and thrust into my arms a great bag of coins, containing the requested amount.

I was moved by this gesture—fool, simple-minded dolt that I was!—and thanked him profusely, with bows and touches to the head and kind words which dismissed as nothing the great work of which I had been unjustly deprived.

But then, at last, a measure of sense came to me, for I remembered once more my vision. Therefore, I determined to investigate the details of the account as he had relayed it to me.

“Sir,” I said, “may I be so bold as to ask you the precise identity of this higher official of whom you have spoken?”

“I fear I cannot say,” he said. “The details of conversations held at council meetings must be kept in the utmost confidence. I have perhaps breached that confidence already even by telling you what I have.”

“You may rely on me to keep my peace on the matter,” said I. “And, since you have already told me most of the tale, it would certainly do no harm to fill in this one small detail.”

“Yes, yes, that is true,” he said. “And perhaps you have a right to know, pa

rticularly considering the unusual nature of the decision. Very well, then—the truth of the matter is we were all most impressed by your glorious plan and were on the verge of putting the issue to the vote. Then the Bishopa of Quebec entered the room, which is her right, for she is bishopa of all East America. Do you know of this woman?”

Although I had met her that very day, I said I did not know of her, for I wished to see what he would tell me.

“Oh, she is a treacherous creature,” said Vulpine. “And though she is a bishopa, yet she is evil and calculating, and much feared and despised throughout the continent. Upon hearing we were about to approve the expenditure, she spoke, insisting a local stonemage receive the commission, and commanding the bishop to reject your own application. This, naturally, he was obliged to do, although it was with the greatest unwillingness. But even so, the rest of us stood firm, for we believed yours was the finest of all the entries. Then the bishopa said she had made her views clear, and if we wished to oppose her, we would reap bitter consequences indeed. You may be assured the bishopa’s threats are not to be taken lightly, for she commands a great army, and it has often been used to wreak destruction in the towns of this region. Indeed it was that very army which burned the north section of our town, in retaliation for a previous offence against her. Therefore, we had little choice but to reject your proposal.”

Now, Eon Vulpine spoke these words in tones that seemed earnest, and his eyes too expressed honesty—so much so, in fact, that I resolved, as a result of this encounter, never again to trust the honesty of people by their faces or by their words. For you see, my dream had predicted he would cheat me. Also, the bishopa had told me how much she had admired my building and even expressed her desire to employ me herself, so it was inconceivable she should have cancelled the construction.

At last, through the power of pure reason, which shines upon all statements like a great beacon, the truth had been revealed: Eon Vulpine was lying. Unfortunately, I reached this conclusion only after I had left his office, and the mood was no longer in me to return and to kill him.

In any event, I knew how to deal with the situation: I sent word to Vulpine that I would have to take a few days to begin plans for the lighthouse, then I boarded my ship and set sail for Quebec, a few score miles west down the river. I took my sack of arrans with me, and I have not returned to Ramport since.

Now, Eon Vulpine had wronged me, that is certain, but you may wonder whether my act of making off with the money was just, for, while it can be an honourable act to kill your enemies, it is never honourable to rob them. Yet consider this: I was originally promised five thousand arrans for the commission, and yet, thanks to his treachery, I received only one thousand. Therefore it was I, not he, who was robbed, and to the tune of four thousand arrans, even after accounting for the sack of coins which he had given me. You can see from this that my actions were honourable.

And they were prudent too, for, while I suffered the loss of a large fortune to the fox, I nevertheless managed, through heeding my vision, and through skilful timing, to minimize the degree of those losses.

The Fourth Part

In Which I Tell Of The Many Good Things Which I Received From The Bishopa And My Execution Of Certain Duties In Quebec

I arrived at the docks of Quebec the next morning and made my way through the city in the direction of Quebec Cathedral, which glittered like a jewel before me.

Quebec is a principally a port for fishing ships and ocean traders. Its industrious people also produce very fine leatherwork. The architecture in the city’s centre is attractive but unremarkable, save perhaps for the Abbey of Saint John the Weak, a long building, which spirals inwards within a great circle, symbolizing his holy vacillations. This abbey houses more than five hundred monks of the New Carolingian Order, the most ascetic in the Eastern Gnostic Church, although you will also see many other types of monks and clerics about the city.

For strategic reasons, Quebec Cathedral lies a half-mile outside the city’s centre. It is a heavily fortified structure, and yet its design displays the utmost grace and delicacy. The walls are a deep blue mineral fusion, laced with platinum tubing enclosing religious scenes of unsurpassed beauty and artistic accomplishment. A magnificent central tower rises six hundred feet above the building, and here are situated not only the bells, which are plated in gold, but also a military lookout post. Four more towers, each three hundred feet high, occupy the corners of the cathedral. These are coated in sheets of purple amethyst, and atop each tower stands a great golden crucifix, cunningly worked so the cross can be quickly pulled down upon a pair of hinged arms, strung, and transformed into a powerful and accurate ballista, capable of hurling an explosive javelin many miles upon the enemies of the church. This I learned only much later of course.

I made my way to the cathedral’s propylon, where I requested an audience with the bishopa. To my surprise and pleasure, the audience was granted within mere minutes. Upon entering the building, escorted by two myrmidons in tunics of red and gold, I was instantly struck by the sumptuous and tasteful decoration, which included rich carpets and a plenitude of fine artworks—including an impressive collection of war scenes by Tybalt.

I was escorted to a great hall, much like a king’s throne room, where the bishopa herself looked down from a richly upholstered dais bench placed more than twenty feet above the floor, topped by an exquisite red baldachin. There were many bishops in attendance, and priests too, and along the walls stood more than fifty myrmidons, with an equal number standing guard on a great balcony which surrounded the room.

As to the woman herself, I was immediately struck by her great beauty and serenity, which seemed to have increased since our previous brief meeting in Ramport. I was also impressed by the great wisdom in her face, something I had not noticed before. Upon her forehead, she bore a few faint lines, which denoted her deep and charitable concern for the many wards of her spiritual domain. She wore deep purple robes, modestly adorned with jewels of all colours, and with fine gold thread, and trimmed at the collar and cuffs with what I first took to be ermine, though later I learned it was the far more precious fur of baby albino sea otters.

She then asked me my business, in a soft voice which carried a lovely vibrato quality.

I then said, “Your Excellency, I had thought my business to concern some financial matter, but now I find this has been swept from my mind as trivial, for, as it strikes me now, the only business which seems of import is to tell Your Excellency how struck and overcome I am by your great beauty.”

Now, at this the bishops who stood in attendance upon the bishopa began exchanging disapproving glances. It was clear, however, the bishopa herself was well pleased by my words, for she gave me a radiant and lovely smile, saying: “Come closer—I wish to see you better.”

I obeyed and climbed the steps to come closer, and she looked upon me for a few moments and then nodded approvingly. “You have a sweet tongue,” she said. “Such language is not normally considered appropriate in addressing me, but I see from your face you spoke in earnest and from your heart.” And then she raised her voice so all in attendance might hear her better and said: “I only wish everyone who addressed me would speak with such sincerity, for I am very often forced to hear false and hypocritical words.” Then, speaking once more to me: “But tell me, Yreth, what was it that troubled you before you entered my hall?”

“Truly, Your Excellency,” I replied, “as I stand now, so much closer to you than before, it is hard for me even to remember my first business. And yet I am loath to waste your time. So, if you will pardon the action, I will close my eyes as I address you, for only in this way will I be able to speak coherently.”

To this plan she gave her assent, and then I closed my eyes and explained to her of the way Eon Vulpine had cheated me of my commission. “Further,” I said, “he claimed it had been Your Excellency who gave the order to cancel the work. Naturally this see

med inconceivable to me, for you spoke to me yourself of your feelings for my modest plans. Therefore, I was forced to conclude that Eon Vulpine had lied to me. This conclusion was supported by a prophetic dream I had in which I was told that what I would lose to the fox I would gain one hundredfold from the bird—though naturally I do not follow such visions blindly.”

She laughed at this, for I unwittingly spoke these words with my eyes still closed.

I then told her how I had minimized my losses by escaping with Eon Vulpine’s payment to me.

She nodded, saying: “Your actions do credit to your integrity and your judgement both, for indeed, you are correct in your suspicions about this man’s lies. It was very proper you should come to me and seek my advice in this affair, for I fear evil is frequently spoken of me in my absence, and such words are all too often believed. Yet now I shall see to it that this Eon Vulpine is sought out and punished for his crime against you and for his slanders against my name. As to your vision, I am certain this was a divine revelation, for my full name is Lenata ad-Hern, and a hern, as you will know being from the east, is a type of bird. Moreover, you will find I am indeed in a position to compensate you for what you lost to Vulpine, although not one hundredfold. But then again, perhaps I am mistaken, for prophetic dreams often contain truths beyond the imaginings even of a bishopa.”

I said, “If I may serve Your Excellency in any way whatever, it will be my privilege and my honour to do so. You have only to state the task and I shall do it.”

“Hear my will then,” she said. “Yreth, I wish you to build for me a second cathedral, for this one has grown too small for my needs. For its design, you must use the plans which you had intended for Ramport—your statue has all the properties of greatness and spirituality which are required for a cathedral, and in any event was far too grand a structure to be wasted on Ramport. I shall pay you five thousand arrans for this task, as the town had promised you, and you shall be given such assistants as you may require.”

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography

The Ultimate Stonemage: A Modest Autobiography